[ad_1]

You’re justified in blocking targeted ads. Malvertising is alive and well and poses a too-big-to-ignore risk to the end user.

For your security (and privacy) you should block ads by default. Here’s why.

Malvertising is malicious advertising. Malvertising intentionally distributes malware and facilitates scams/phishing. There are many ways malvertising can be “carried” out; some commonly seen examples of malvertising include malicious search ads, malicious social media ads, and other malicious targeted ads displayed on websites.

Malvertising does not exclusively rely on user interaction to download malicious scripts. Malicious scripts can be downloaded and executed on user devices without explicit user consent or interaction. These scripts can in turn call second-stage malware and are commonly known as drive-by downloads.

Perhaps the most dangerous part of malvertising is that it can appear on any advertisement on any website – including extremely popular, well-known websites. This can happen without the website being breached directly by itself – especially if third-parties are used to serve third-party ads. Malvertising can also occur on websites that manage and run their own “first-party” ad platforms, like many mainstream social media platforms such as Instagram and TikTok.

In recent years, there has been a noticeable increase in search engine malvertising. So much so that in December 2022, the FBI put out a public service announcement warning the public of threat actors abusing search ads to deliver malware, ransomware, and steal sensitive information such as login credentials.

Given Google’s dominance across search and the associated ad space, threat actors (bad guys) regularly abuse the ecosystem as it gives maximum return on exposure. For similar reasons, Bing Ads sees its fair share of abuse too, but due to marketshare we can assume prevalence is lower – there is more return on investment with abusing Google Search Ads.

Abuse of these ecosystems ultimately means a large audience will see these malicious ads, increasing the likelihood someone will click on them. The more people click on them, the more people are redirected to the phishing/malicious site.

Brief Overview

Search engine advertising is relatively simple on the surface, though there are a whole lot of nuances I will not get into here.

Advertisers can have their ad – usually a bid on a keyword – displayed near “organic” results. Typically, the advertiser pays the platform for every click on their search engine ad. The more in demand or popular the keyword, the higher the cost per click (CPC).

In a non-malicious scenario, users are directed to the advertiser’s website/property once clicking on the ad. For example, you search “cybersecurity” and I bid on that word as an advertiser. You see my ad, you click on it, and then you are redirected to my website.

But what if the advertiser is a threat actor or otherwise malicious? Well, once clicked, users are typically directed to a malicious domain that may drop malware or trick users into divulging sensitive information. Except it’s not quite as simple as directing users to a malicious site from the immediate get go.

In many cases, the threat actors employ cloaking techniques, linking users to a “benign” website before redirecting them to the true phishing/malicious domain. Hovering over the link won’t necessarily work to tip you off to a malicious domain, your browser’s “safe browsing” may not have this first “benign” domain in its “bad list,” and Google’s detection algorithms can’t explicitly detect the malicious domain unsuspecting users are forwarded to.

Source: Guardio Labs

This widespread and ever-growing issue of rogue search ads is a multi-faceted issue with many moving parts, but we can kind of break it down into:

- Paid ads/”sponsored” ads are at the top of the search results page

- Ever-evolving methods to circumvent existing (albeit, lacking) controls

- Lacking ad-screening controls/policies

These factors feed into each other and are not necessarily a linear cause-and-effect relationship. There are other factors, such as user privacy considerations and platform algorithms, with influence as well.

Sponsored ads for keywords on search engines are generally placed at the top of the search results pages, ahead of “actual” or “organic” results.

This is a problem because there is overwhelming evidence that approximately 28% of users click on the first search result on the search results page. Therefore, if a malicious ad is at the top of the sponsored results section – or even just above the organic results – there’s a far higher chance an unsuspecting user may click it.

For example, when using Google Search for the keyword “ransomware,” these are the sponsored/paid results:

These are the organic results for the same search for the same keyword on the same page. Notice how official government sources such as CISA (US) and the NCSC (UK) are below the paid results:

In fact, the “organic results” were below the paid ads, summarized definition of “ransomware,” and Twitter/X posts containing the word “ransomware.”

Search Engine Optimization (SEO) is an entire industry dedicated to using “best practices” to rank higher on search engine results pages for increased traffic.

Search ad or result?

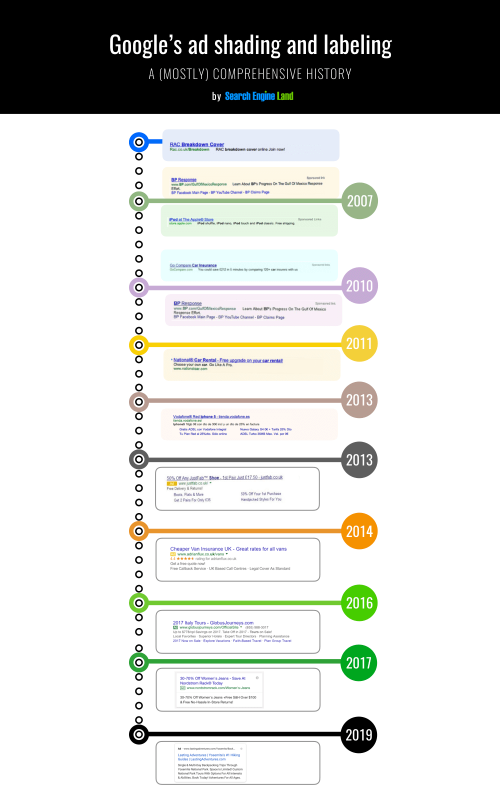

Another issue is sponsored/paid ads on search results pages appear to blend in with organic results surprisingly well – especially at first glance. Paid search ads seamlessly blending in with organic search results seems to be a trend in recent years.

For example, Google has removed more “obvious” signs indicating a result was a paid advertisement. In October 2022, Google has removed “Ad” from paid search advertisements on mobile altogether, replacing “Ad” with… “Sponsored.”

It also doesn’t help Google has continuously changed the appearance of paid ads on search results over the years. Overall, paid ads/sponsored results in Google Search look more similar to actual results than ever before.

Source: Search Engine Land

So, what does this mean? By abusing search ad platforms, rogue ads pointing to malicious websites are in prime position for user viewing and interaction. Remember, many users have a tendency to click the first search result – and since paid search ads blend in with search results so well and are often displayed first on the “results page,” they may inadvertently click on a search malvertisement.

It may be easy to assign the solution as “people should pay attention more,” but research indicates most people skim written content on the web. People may also implicitly trust what a brand such as Google puts in front of them and not be “on guard” when clicking results/paid ads in a search – they may not even be aware they are clicking on an ad!

As with just about anything in the cybersecurity space, threat actors are constantly evolving their tactics, techniques, and procedures – whether their “evolution” is using new and improved methods to accomplish their goals or reaching into the old trickbag to use “old methods” with (or without) a spin.

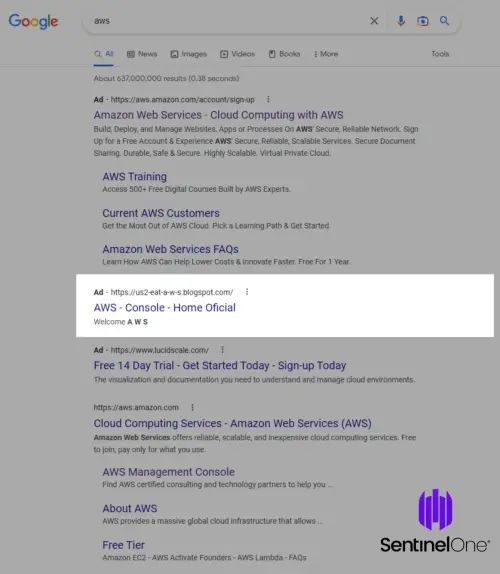

In February 2023, Sentinel Labs reported a phishing campaign targeting Amazon Web Services (AWS) logins using Google Ads. When searching for “aws,” the malicious ad ranked second – right under the official Amazon ad on the search results page. At first the ad lead directly to the phishing domain, but then later the threat actors added a redirection step to evade Google’s detection schemes.

Source: Sentinel One

In July 2023, Sophos reported threat actors were observed using Google and Bing search ads to deliver trojanized versions of legitimate software such as AnyDesk (a remote desktop tool) and Cisco AnyConnect VPN. The trojanized .iso files were primarily distributed using hacked WordPress websites and landing pages. The trojanized software would then download second-stage malware.

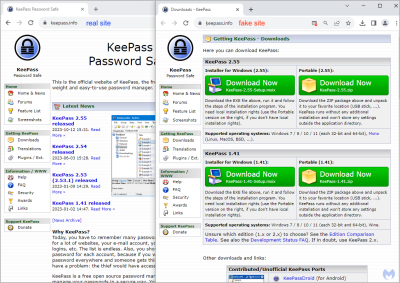

In October 2023, Malwarebytes discovered a malicious search ad campaign abused punycode to register a domain very similar to the official keepass.info domain. The fake domain was promoted via the sponsored results (paid ads) section of Google Search results pages and used to distribute signed malware to unsuspecting users who clicked on the ad.

Source: Malwarebytes

However, the punycode character would have only been visible after clicked on the malicious search ad; Google Ads did not render the punycode character in the ad on the search results page. So, to users viewing the search ad on Google, it indeed looked identical to the legitimate keepass.info domain.

Punycode is an encoding method for representing Unicode using the limited ASCII character subset for internet domains and hostnames. It allows non-Latin characters to be used with domain names.

There’s also evidence that threat actors have compromised “verified” adsense publishers and used these hijacked (and verified/trusted accounts) to publish rogue or malicious ads. In November 2023, Malwarebytes discovered a piece of a larger campaign (specifically, targeting popular software utilities such as CPU-Z) where Google Ads was abused to direct unsuspecting users to a domain serving malware.

Source: Malwarebytes

The threat actor used cloaking techniques to skirt around Google’s detection algorithms; users identified as prime targets were forwarded to a fake Windows news site, which enticed users to download information stealing malwares. Malwarebytes suspected the “advertiser” was either “compromised” or a fake identity that skirted around Google’s verification controls.

From a privacy perspective, it is generally advised to move away from using Google and Bing Search as search providers; users are certainly encouraged to use private search providers instead.

However, while not using Google Search is a great move for improving your privacy, it is not enough to escape potentially viewing or interacting with malicious ads of its own. Third-party search engines, whether private or not, drawing from Google’s index may also serve Google ads on their own results pages. Thus, without using adblocking methods, the possibility a user could accidentally click or otherwise interact with them remains high.

Unfortunately, Google and search engines drawing from Google’s search index are not the only search platforms affected. Bing Search suffers from the same issue, though less prevalent due to Google’s massive marketshare and reach. Therefore, it is possible for search platforms proxying Bing’s search results to also inadvertently show rogue or malicious Bing Search ads.

Using adblocking methods is the most reliable way to stop seeing such ads, whether on Bing or Google directly or on a third-party search provider drawing from these indexes.

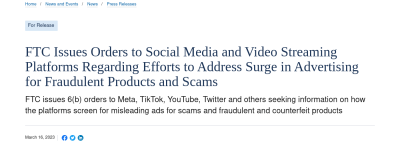

The US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) estimates the amount of fraudulent ads appearing on social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, TikTok, Twitter, Twitch, and others is “a whole lot.”

In March 2023, the FTC issued orders for social media platforms to report how they let users know an ad is… well, an ad. The FTC stated this order was issued in response to the reported surge of fraudulent products and scams promoted via ads on these platforms.

Social media platforms have also faced scrutiny for their ad screening and ad approval processes and are consistently accused of running ads with disinformation/misinformation, ads that go against their own established policies, or ads that facilitate scams and fraud. Social media ads are also abused to trick users into download malware and often leverage legitimate brands to do so.

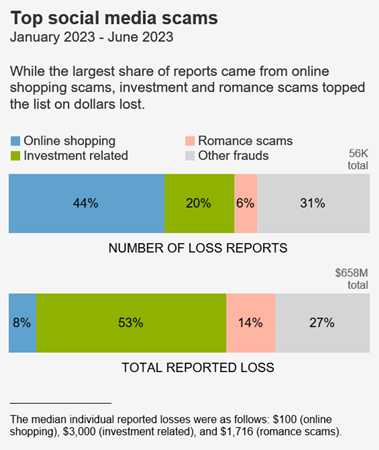

According to the FTC, consumers reported losing $1.2 billion to fraud originating on social media in 2022. According to FTC data, this was more than any other contact method in 2022.

Overall, since 2021, approximately 1 in 4 people who reported losing money to fraud said it started on social media.

The FTC states scammers can run ads using tools available to advertisers on social media platforms to systematically target individuals based on personal details, such as age, interests, and past purchases.

(After all, the most popular and traditional social media platforms collect this information and use it for advertising purposes – which is a separate issue entirely.)

In the first half of 2023 alone, the FTC reported the most frequently reported fraud loss was from people who tried to “buy something marketed on social media,” accounting for approximately 44% of all social media fraud loss reports during this time period. Investment scams, peddled via “financial gurus” and displayed ads were the second most reported fraud loss.

Source: US FTC

In December 2020, Time Magazine ran a story about threat actors stealing photos from online marketplaces such as Etsy and reusing them in fraudulent social media ad campaigns. When users saw these ads, they ordered the items shown in the lifted pictures; they either received extremely fake knock-offs or nothing at all.

The primary site in question in this particular story here was Facebook. Allegedly, groups dedicated to reporting similar scam ads and Facebook pages were ignored by Facebook representatives. The ads promoting the scam ecommerce stores continued; we can probably safely assume more people fell victim to these scams even after Facebook was made “aware.”

Investment scam ads are also prevalent on social media platforms – Instagram and Facebook (both owned by Meta) in particular.

Instagram and Facebook are hotbeds of investment scam ad related activity, the ads luring users to websites inviting users to invest a sum of money for near immediate returns – only for the money to be lost to the scammers.

TikTok doesn’t escape abuse of its promoted posts or ad ecosystem either.

TikTok has also been a growing pool of similar rogue ad activity prevalent on Instagram and Facebook, with scammers reportedly launching ads on the platform to promote fake cryptocurrency investment opportunities. In September 2023, TikTok was flooded with numerous posts (likely using TikTok’s promoted feature) peddling fake cryptocurrency giveaways. The attackers leveraged well-known figures like Elon Musk to give “legitimacy” to the scams.

YouTube (owned by Google) also sees its fair share of scam ads.

In November 2023, YouTube still ran ads promoting Quantum AI cryptocurrency scams.

Prominent YouTubers have also called YouTube (Google) out on promoting scam ads. In June 2022, MrBeast criticized YouTube for continuing to run fake giveaway ads that used his likeness without explicit consent. He has called YouTube for similar inaction on scam ads using his persona in the past as well.

Unfortunately, rogue social media ads are not just limited to peddling ecommerce and investment scams. Rogue social media ads have increasingly been used to peddle malware to unsuspecting users who interact with these (click) malvertisements.

In July 2023, Check Point reported that threat actors were abusing Facebook pages and ads to impersonate generative AI brands like ChatGPT and Midjourney to trick users into downloading information-stealing malware.

Source: Check Point

In October 2023, Bitdefender reported threat actors compromised business Facebook accounts to run ads as part of a NodeStealer (an information stealing malware) campaign. These ads often used “provocative enticement meant to sway users into clicking on an infected link.” Clicking on the ads downloaded an archive containing a malicious .exe executable on the victim’s machine.

Source: Bitdefender

Social media ads and disinformation/misinformation

Misinformation is rampant – even without the reach boost of ads – on many social media platforms. For example, the sudden onset of Russia’s invasion into Ukraine saw an influx of misrepresented images and even the use of generative AI to spread “fake news” surrounding the invasion. This “fake news” was spread by users (knowingly or unknowingly) via traditional platform sharing options (think, retweeting, reposting, etc.)

However, the spread of misinformation/disinformation isn’t limited to bots or legitimate users sharing misrepresented media or content. Alongside scams, paid ads have been used to float misinformation on traditional social media platforms. Those pushing “fake” ads can range from “regular” users to nation-state backed threat groups.

Those pushing disinformation/misinformation ads can leverage the same tools as “legitimate” advertisers to tailor ads to specific demographics – just like the scammers posting ads on many social media platforms. As long as the money reaches the platform, in many cases the ad will run until reported – but how many people have seen the ad, interacted with it, and perhaps even shared it with others by that point?

Allegedly, Facebook and TikTok in particular “failed to block advertisements with “blatant” misinformation” about when and how to vote in the US midterm elections in 2022. In October 2023, at the outbreak of the Israel-Hamas war, search terms such as “Israel Palestine” on TikTok displayed “numerous examples of such sponsored content.” Sponsored content is mixed with other content on the platform and is relatively cheap to promote.

Even after the US 2016 Presidential Election, where Russia had attempted to interfere with the election, Facebook continued to be the social media platform of choice for Russian cyber operations spreading misinformation/disinformation specifically targeting Americans.

In 2020, Facebook allegedly allowed ads containing misinformation about the coronavirus pandemic to circulate on the platform. In 2022, the non-profit watchdog Tech Transparency Project discovered Facebook ran associated ads when searching for white supremacist groups – despite claims to have banned such groups and associated “hatespeech” from the platform.

Social media and search engine ads have something in common – in most cases, the platform on which the ad is displayed, serves the ad itself. While the ad frequently points to the website or property of a third party, the ad itself is not served by the third party.

The “third-party ads” referred to in this section generally refer to programmatic and targeted advertisements displayed on websites. In many cases, these ads are served by an ad platform that is third-party to the website (and visitor). Generally, the website owners insert code designed to pull content from the third party – the content pulled is ultimately hosted and directly managed by the third party.

This is why, if you view the developer’s console in your browser, you will generally see “connections” to websites that aren’t a part of the domain displayed in your address bar. Though, this frequently happens outside of the purpose of just serving ads; many websites load resources from other servers not directly connected to the main domain. So, just because a website is initiating third-party connections, it doesn’t necessarily mean they are serving ads, tracking, or fingerprinting you (though it can certainly be the case…)

Note: Websites aren’t necessarily limited to only running ads from advertising platforms; they can run “first party” ads themselves, such as directly selling banner space to companies. Some websites do both, but many opt to use third parties to run ads.

The primary issue with loading any third-party content is that there exists implicit trust between the website owner and the third-party. In the end, the website owner(s) do not have direct control of the third-party content being served; with ads, they do not have direct control of the ad content being served to visitors.

What happens if the ad platform serves unwanted content? Better yet, what happens if the ad platform serves malware on the otherwise uninfected/un-breached website? Enter: more examples of malvertising!

In July 2015, it was reported that as a trend, threat actors were increasingly targeting online ad networks with the goal to infect end users; not necessarily the websites serving the malicious ads themselves. In particular, news sites and entertainment sites were the most attractive targets due to the large volumes of traffic they see. More traffic = more exposure = higher likelihood to infect more users.

In March 2016, news sites like the New York Times and the BBC served ransomware variants via displayed ads. The malware was distributed via multiple ad networks.

In July 2021, major news sites including HuffPost and New York Magazine served pornographic videos instead of intended content. These news sites relied on a third-party, vid.me to embed streaming videos on their websites. At the time, vid.me had been defunct since 2017, but it was registered a month prior to the story to redirect all vid.me links to a porn site.

In November 2022, it was reported hundreds of news sites were serving visitors malware via displayed ads. The common source for all these news sites was a single media content provider; the media content provider was compromised by malicious threat actors. This compromise allowed threat actors to push their malware to these news sites who were otherwise “unhacked.”

In the case of dealing with malvertising, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

Blocking ads and associated scripts before they can ever load in your browser or on your device is the best method for dealing with malvertising. If blocking is not possible, ads should be treated the same as suspected phishing links.

Actions such as avoiding clicking or otherwise interacting with ads are not enough to avoid the security risks associated with them. Again, as described earlier, the loading or simple viewing of an ad could load malware onto a machine or exploit vulnerabilities in the browser to execute malicious code by an attacker.

Therefore, the best mitigation for users to follow is to block the ads by default. This prevents the ads – and potential malware embedded or delivered by them – from loading, reducing compromise risk stemming from the many variations of malvertising.

Ads can be blocked in the browser, on the device, and on the network. At minimum, users should consider blocking ads in any browser they regularly use. If possible, it is also good practice set either your router (or if not accessible, your devices) to use a DNS resolver with filtering capabilities. Many DNS server providers have servers capable of blocking resolution or connection to known ad, tracking, or malware serving domains.

Blocking ads in the browser

For blocking ads and trackers inside the browser, installing extension/add-on uBlock Origin is advised. uBlock Origin is an open-source wide-spectrum tracker blocker with a low processor footprint that aims to give the user control of what content they see.

uBlock Origin is available for Chrome (Chromium) and Firefox (Gecko) browsers.

Note: With the impending rollout of Manifestv3 in June 2024, Google Chrome users will reportedly experience less effective adblocking capabilities from extensions.

Some browsers have built-in adblocking functionality as well. uBlock Origin can also be used on these browsers.

Blocking ads via DNS

Most default network settings use the default internet service provider’s (ISP) DNS resolvers, which are likely unencrypted and do not provide meaningful domain filtering abilities. Users are encouraged to use DNS resolvers capable of blocking malware and ad/tracker-serving domains.

Additionally, users are encouraged to use DNS resolvers that encrypt queries while minimizing information sent to root DNS servers. If this is not possible to set on the network (usually via a router), many devices allow users to set custom DNS servers/resolvers, overriding the default options for the connected network.

More details on adblocking on the browser, device, and network levels can be found in an associated Avoid the Hack guide for blocking malware and ads.

Most adblocking software relies on filter lists to blocking loading of associated advertisement material, which can also include scripts/code dedicated to tracking and/or fingerprinting.

Some adblocking software also combine preemptive rules, such as subdomain names “likely” to serve ads or trackers; for example, a server with hostname ads.randowebsite.com could be reasonably assumed to serve ads. Many also allow users to specify entire (sub)domains to block or place on an allow list.

Implementing filter and blocking lists ultimately depends on a user’s threat model and overall goals. Blocking lists outside of ads and trackers certainly exist. Many have specific themes, including (but not limited to):

- Blocking domains known to serve malware

- Blocking gambling and/or sexual content

- Parental control themed lists, which may block popular entertainment sites

- Blocking known phishing domains

- Blocking recently registered domains

In any case, it is strongly advised to use lists that are maintained and regularly updated as advertising, tracking, and other unwanted content (sub)domains frequently change. Most adblocking software will fetch updated lists automatically.

Users are encouraged to view the Avoid the Hack blocklist collection for more information and block list suggestions.

Blocking advertisements may not be possible on all websites due to any number of reasons. When blocking ads is not possible, users should give displayed ads the same treatment as they would for suspected phishing links:

- Avoid clicking on displayed advertisements

- Ensure any downloads came from an official source; use checksums to verify the integrity of downloaded files

- Beware of anything that is “too good to be true,” such as investments promising 100% returns and absurdly low prices for goods known to be expensive

From a cybersecurity perspective, you are far better off blocking ads than not. That’s it.

Since malicious advertisements can compromise users with or without user interaction, it’s better to stop them from loading and potentially infecting a user’s browser and/or device than it is to remedy said infection.

With that said, stay safe out there!

[ad_2]

Source link

avoidthehack.com