[ad_1]

Welcome to the world of online/digital privacy!

Like its sister guide for cybersecurity, this privacy guide was written for complete privacy novices in mind. It is designed to be a starting point for anyone new to the world of online privacy.

It also contains actionable advice for getting started on your privacy journey without the need for threat modeling (though it is certainly advised to set a direction for your efforts eventually.)

When it comes to improving privacy, absolute novice advice often includes “creating a threat model.” This is actually great advice as threat modeling allows you to focus on achieving your goals while keeping in scope your personal resources, such as time and money.

However, there are “privacy 101s” users can and absolutely should take prior to sitting down and figuring out a threat model that works for them. These basics have great and potentially near-immediate “returns” when starting out one’s privacy journey. Threat modeling should take place after these “basics” are in play.

The steps outlined in this guide are basic, highly recommended privacy steps anyone can take regardless of an established/not established threat model:

Use a privacy-oriented browser

Use a secure/encrypted email provider

Use private search engines

You do not need to have a threat model in place to take action on the points listed in this guide.

For example, it would make little sense for users to switch to a privacy-friendly operating system yet continue to use Google Chrome in their day-to-day browsing activities. Likewise, it would make little sense for users to continue to use privacy-unfriendly email services while signing up for more private/secure services.

Above all else: take your time. Small changes are easier to manage and retain over big, “dramatic” changes. Privacy is a journey.

Before proceeding, you should ensure you’re hitting the baseline for personal cybersecurity.

Security and privacy overlap, both inside and outside the digital space. It’s highly advised to review and shore up basic cybersecurity practices alongside improving your privacy, if you haven’t done so already:

- Develop good password management skills

- Use multifactor authentication (MFA)

- Keep devices/software updated

You should master these basic personal cybersecurity best practices prior to starting on your privacy journey or taking any of the steps outlined here.

Basic security naturally lends itself to privacy. I strongly recommend viewing the getting started guide (the sister guide to this one) on security.

Put into context, it would make little sense to use a privacy-oriented browser and all the features such a browser may have to offer, but continue to reuse passwords across online accounts. Likewise, enabling MFA at least on sensitive accounts protects the account from unauthorized access – by extension, this also protects the data inside that account from access by malicious actors.

It’s also viable to implement this guide and the cybersecurity one at the same time for simultaneous improvement for your privacy and security!

Implementing better basic security practices can improve your privacy as a secondary benefit by helping to prevent and lock down your accounts and devices.

Your privacy can be compromised when security is weak or lax. With weak security, unauthorized users obtain access to your online accounts – for example, they could collect personal identifiable information (PII) from unauthorized access to your accounts!

Privacy-oriented browsers are web browsers that respect user privacy.

Privacy-oriented browsers generally aim to share as little data as possible with the websites users visit. By default, they usually mitigate the effectiveness of common tracking/fingerprinting methods and preventing unneeded information exchange between the browser and the web server.

Privacy-oriented browsers also limit data collection and “phoning home” and telemetry activity on their backend (in this specific case, I am using “backend” to refer to the side where users don’t necessarily directly interact with the browser), preserving your privacy as a user.

Plenty of browsers phone home potentially identifying and sensitive data such as (but not limited to):

- Search history

- Search keywords

- Browsing history (URLs visited)

- Location data

- Network information

- Downloaded files information

- Device information

- Unique identifiers

On any internet-connected device, such as your home computer or your smartphone, your most used application is probably your browser, which makes privacy in the browser highly important. URLs visited and browsing history can be particularly sensitive and the unintentional/unaware sharing of such information greatly undermines privacy.

If someone knows your web they can learn a disturbing amount about you. This is compounded by combination with other information details — such as demographics, location history, device information, usage analytics just to name a few. The privacy issue is even further compounded if this data is shared with others (even if “anonymized”) or is used for other purposes, such as tracking and serving targeted advertisements.

Understanding browsers

At its core, a browser is software used to easily access the internet. You’re probably reading this post in your browser, where your browser pulled together JavaScript, HTML, and CSS resources from the Avoid the Hack web server to render this web page as you currently see it.

Modern browsers do more than just chaining together requests and render web pages and allowing easy access to the internet. You’re probably familiar with some of the extra functions your browser of choice can perform more so than you think.

Think about all that is possible to do in your browser without ever switching to another app or program:

- Have nigh-unlimited tabs

- Block/store cookies

- Save bookmarks, passwords, temporary data

- Autofill of information

- Sync with other services and devices

- Often have extensible functionality (browser plugins – Add-ons and Extensions)

- Audio/Video calling without downloading additional software (via WebRTC)

Note: Not an all inclusive list.

Due to their functionality and capabilities, modern browsers can easily be more complicated than entire operating systems. With such sophistication, arises other issues. Many of the “mainstream” and widely popular browsers out there tend to “overshare” data with visited websites and developers (of the browser), ultimately compromising user privacy.

Browser privacy issues

Underneath all that complexity, the widely popular browsers – such as Microsoft Edge and Google Chrome – may transmit data without expressed user knowledge or consent; in many cases, they may engage in their own data collection and “phone home” to remote servers without explicit user knowledge.

Browsers can leak and transmit data predominately on two fronts – the front-end and the back-end. These terms are used loosely in this section to try to easily differentiate the difference between what the user sees and “controls” versus what they can’t.

Leaking information to websites

On the “front-end,” particularly with visiting websites and establishing connections with web servers, browsers can over-communicate information; they may provide the web servers unneeded and/or unrequested information, such as, but not limited to:

- System fonts

- Timezone

- Location information

- System device information (is there a microphone?)

- Previous visited/”referred” website (via

refererinformation) - Detailed operating system information

- Temporary storage

In turn, this information can be used to identify and track users across multiple sites. Many websites are “aware” of the data browsers may overshare and often engage in silent data collection to gather information to fingerprint (identify) and track users.

Once collected, depending on the website/service, this data may be used for other purposes – such as training algorithms, tracking user activity and browsing history (even for “legitimate” purpose) or compiling user profile for sharing/selling to others. A primary issue compounding this is expressed user knowledge and consent of such data collection for such purposes.

Of course, the fault here doesn’t 100% lie with the browsers; websites also share a piece of the blame. Just because a browser “overshares,” necessarily mean the website has to use it for fingerprinting or tracking purposes. However, it’s often best to never transmit the data in the first place, as it becomes nigh-impossible to control it once “shared.”

Telemetry and data collection issues

On the “back-end,” browsers can send information to remote servers, such as one owned by the developer or maintainer.

Not all instances of a browser’s back-end communication are privacy invasive or malicious; for example, a browser may make calls to its infrastructure servers to check for relevant updates. Updates frequently bring security patches, bug fixes, quality of life improvements, and new features to browsers. But many users may forget or simply neglect to manually initiate requests for updates in the browser.

However, information phoned home by the mainstream/widely popular browsers can and frequently contain identifying (and sensitive) information.

In some cases, popular but privacy-unfriendly browsers like Microsoft Edge and Google Chrome may phone home browsing-related information and unique identifiers. They are not alone, however as some “alternative” browsers may phone home similar information, such as unique identifiers coupled with the IP address of the machine where the browser is installed. They may also employ different mechanisms for effectively collecting browsing histories of users.

Privacy-oriented browsers address privacy issues on the both the frontend and backend of the browser. Privacy-oriented browsers frequently employ additional measures, such as coming bundled with ad/tracker blocking mechanisms by default. Privacy-oriented browsers also limit their data collection and general phoning home activity on the backend.

The definitive answer to this question comes from a mix of which devices you use, customization options (including browser plugins), and some personal taste. Naturally, some browsers are better than others when it comes to privacy.

Basic and universal criteria that should be expected of a privacy-oriented browser includes:

- Open-source source code.

- Regular updates.

- Not collect browsing history.

Privacy-oriented browsers should also provide defense against the myriad of tracking mechanisms employed by various websites, web services, and web apps. This can include enabling a native ad/tracker blocker by default or providing fingerprinting resistance.

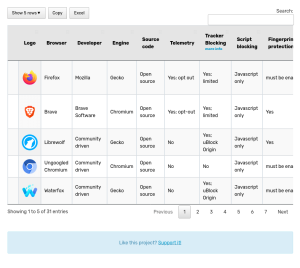

Avoid the Hack has recommended browsers for major operating systems. Browsers listed must be open-source, regularly updated, out of testing stages, provide customization, and engage in limited telemetry or data collection:

Avoid the Hack also maintains the Private Browser Comparison Tool, which lists alternative browsers. The browsers found here are not necessarily recommended. Information presented is meant to give the user relevant details for making informed decisions regarding their privacy-oriented browser choice.

Avoid using Microsoft Edge and Google Chrome

For privacy reasons, generally, it’s advised to avoid using Google Chrome and Microsoft Edge. These two browsers are typically regarded in the greater privacy community as the worst browsers for overall privacy.

Microsoft Edge and Google Chrome both engage in excessive telemetry, assign/extra identifiers from your devices, and collect potentially sensitive information which can include your URLs visited – which effectively translates to your browsing history.

Microsoft Edge

Microsoft Edge transmits the device’s universally unique identifier (UUID) to Microsoft’s servers. UUIDs are used to identify a device on the internet and are more specific than IP addresses. UUIDs are also difficult to change, making it a rather robust way to fingerprint a particular device across most changes – such as browser reinstalls.

In April 2023, it was revealed Microsoft Edge sent visited URLs to its Bing API website, bindapis.com. While this leak may not have been intentional, it does show the data Edge can collect on users.

Microsoft’s “SmartScreen” sends the full URLs of visited webpages to Microsoft’s servers. This URL is not hashed, though Microsoft claims they strip PII if included in the URL when possible. Fortunately, SmartScreen can be disabled.

By default, outside of SmartScreen, Edge sends browsing data to Microsoft if signed in and when syncing to Microsoft’s cloud is enabled. The predominant issue is Microsoft owns the keys for server-side decryption of stored data; it’s not in encrypted prior to leaving the device.

Edge’s search autocomplete functionality can send data about web pages visited to servers apparently unrelated to search autocomplete. While this can be disabled, it’s enabled by default.

When using Edge’s InPrivate feature, Microsoft collects “diagnostic” information as according to Windows diagnostic data settings and Edge privacy settings. Keep in mind that users cannot completely opt-out of sending diagnostic data from Windows to Microsoft:

Google Chrome

Google Chrome sends session and browser instance identifiers, which could include the websites visited, to its servers upon installation. These identifiers are used to uniquely identify users and are persistent across browser restarts.

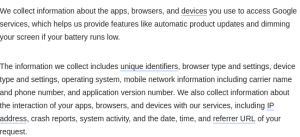

Google collects usage statistics in Chrome by default. These usage statistics can include link clicks and preferences. Google also collects data about the device, which can include the IP address, system activity, date, and time.

Chrome’s search prediction is enabled by default and can send data about web pages you visit as well as search terms to Google. This turns into a double whammy if your default search provider is Google, as this data becomes easily aggregated into your “profile.”

Google’s Enhanced Safe Browsing sends URLs, portions of page content, and system information to Google. It can go as far as to check for “risky” URLs, downloads, and browser extensions.

In September 2023, Google implemented the “Privacy Sandbox” for Chrome. Many respected parties advocating for user privacy have called the the title deceiving due to its use of “privacy” as it can be described as browser tracking 2.0 and is not a move away from tracking and profiling user browsing habits altogether. While the Privacy Sandbox aims to make third-party cookies obsolete, it also centralizes the tracking many third parties performed via third-party cookies into Google’s control.

In June 2023, Google was sued for allegedly tracking users who use Chrome’s “Incognito Mode” more rigorously and deceived users into believing it provided more privacy protections than it actually did. Google settled this lawsuit in December 2023, after its move to get the lawsuit dismissed was rejected.

What does this mean? Microsoft and Google know who you are and your web-browsing habits.

By extension and in many cases, they also learn your search history and how you interact with websites and their browsers themselves. They can and do collect this data even when you are not signed into your respective Microsoft and Google accounts in the browser. As mentioned, Microsoft Edge and Google Chrome phone home identifiers, usage statistics, and URLs visited by default; there is only so much you can opt-out of within the settings.

Neither Edge nor Chrome make it easy or practical to tweak privacy settings in the user’s favor. Therefore, it is hard to reign in each browsers’ data collection and phoning home actions, unless more technical means are applied – which simply isn’t feasible for everyone. Even when tweaking settings in either browser, they both have a low ceiling for privacy.

Apple Safari

What about Safari? Admittedly, Safari falls into a weird spot, where it is closed-source, arguably “not as bad” as Google Chrome or Microsoft Edge, and Apple has a better overall reputation in the privacy community.

That said, just because it is “not as bad,” doesn’t mean using Safari is beneficial for your privacy. Safari has a relatively low ceiling for privacy “hardening” and overall tweaking/customization. There’s evidence Safari phones home web browsing-related data to Apple, tagging requests with identifiers by default.

A reason to use Safari would be to maintain a less unique fingerprint on iOS devices. All browsers on iOS are “forced” to use the same WebKit rendering engine as Safari, so the actual “variety” of different browsers and engines is far less relevant on iOS devices. However, it seems Apple is considering dropping the requirement for browsers to use WebKit on iOS.

Understanding “Incognito Mode”

“Incognito Mode” or private browsing is a browsing function where the browser does not store temporary browsing data outside the current browsing session.

“Incognito Mode” or private browsing does not store:

- Cookies

- Local search history

- Browsing history

For example, if you were to login to your bank account using a private browsing window, close it, and then open a regular browsing window, you will find that you are not logged in (because the cookie storing your session information was not saved).

Similarly, if you were to visit avoidthehack.com in a private browsing window – and you hadn’t visited before in a regular window – when you open a normal browsing window, you won’t find avoidthehack.com in your recent history. This is because private browsing doesn’t save local browsing history between sessions.

“Incognito Mode” refers to the private browsing function for Chrome, but has become somewhat of a catchall for private browsing in general:

- Incognito Mode is private browsing for Chrome and most Chromium-based browsers

- Private Browsing is private browsing for Firefox and most Gecko-based browsers

- Private Browsing Mode is private browsing for Safari

You may think or hear others say they use Incognito browsing and therefore their data is private. This is not the case as Incognito Mode only affects local storage and browsing/search history.

“Incognito Mode” or private browsing is not a viable tool for improving security or defending against advanced fingerprinting/tracking methods.

“Incognito Mode” cannot mitigate defects in browser security (such as not staying up to date with security patches) or defend against malware or spyware.

While Incognito Mode will wipe local search history when closing the window, it does not 1) prevent queries from being logged by the search provider or 2) stop any other data collection from search providers (such as IP addresses, fingerprinting practices, etc).

Incognito Mode does not stop backend telemetry, either. As mentioned above, there is evidence users who use Incognito Mode in browsers such as Edge or Chrome are “specially” tracked.

We live our lives in our inboxes; there’s a wealth of information about just about every facet of our lives in our email inboxes.

By combing through the messages in your inbox in just a “read-only” type of status, someone can learn:

- The accounts you’ve registered for

- This can include sensitive accounts such as credit card accounts, bank accounts, AppleIDs, etc

- Employment information

- Contact information (who you talk to), such as family members and close contacts

- Purchase history (receipts from e-commerce merchants)

- Personal identifiable information: address, address history, mobile phone number, etc

Many email service providers have access to your inboxes. Often, users must “trust” by default email providers won’t access, share, or otherwise use the copious amounts of data in their inboxes for other purposes. But this isn’t a guarantee that they won’t do so – and they may not provide notice when/if they do.

Additionally, most email providers do not mitigate or limit “oversharing” of information when using emails – such as reducing excess information found in email headers, of which can unintentionally expose IP addresses, device information, and email client information, when sending a message. They also do not mitigate the various tracking mechanisms received email may employ when opening messages or clicking on links.

Secure email providers often employ zero-knowledge encryption for users’ inboxes. Zero-knowledge encryption means that no one without the proper private keys has direct access to any given user’s inbox – including the servers hosting the inbox. This is in stark contrast to many free email providers out there, who may know/access your data because they have the decryption keys.

Using zero-knowledge encryption allows many secure email providers to lend themselves to privacy simply because they can’t access users’ inboxes. Of course, this is operating under the assumption the private key is never exposed to the provider – whether intentional or accidental. Usually, with reputable providers, we can reasonable assume the private key used to decrypt your messages and inbox is not exposed.

While there are email providers more privacy-respecting than providers like Gmail or Outlook.com, it’s best to use an encrypted email provider – specifically, one that uses zero-knowledge encryption. This ensures you don’t have to trust the provider’s “good word” that they will not access your inbox or message contents.

Generally, secure email providers have more limited data collection practices when compared to more traditional free email providers. In many cases, even for account creation, secure email providers collect limited data or no personal information at all. Some allow anonymous account creation.

Most secure email providers also provide robust email tracking protections, whether by their own filters or via their email clients. While most free and popular email providers do provide spam protection, this is not necessarily the same as preventing trackers embedded in legitimate emails (think, marketing or newsletters) from tracking open rates and click rates.

Similarly, since email as a protocol transmits a wealth of metadata, secure email providers limit metadata included in sent messages. As mentioned previously, such metadata found in sent messages (email headers) can unintentionally share information like email client information and IP addresses with the routing servers and recipients.

If using one of the popular email service providers – such as Outlook or Gmail – these service providers have access to your inbox, metadata associated with messages, and even direct message contents themselves.

These “free” email providers own the keys for the encryption and decryption of your data, so you are essentially placing trust in the email provider’s word not to abuse this. However, while its doubtful that these email service providers actively read email contents (despite having the capability to do so), many do in fact scan users’ inboxes and messages.

Reasons for inbox scanning range from fighting spam and malware, enabling convenience factors, to harvesting metadata for machine-learning algorithms. The underlying issue with any of these reasons is that, in any context, they blatantly violate user privacy because they’re scanning… everything.

So, the email from grandma asking how you’re doing, the poorly written phishing attempt email, the emailed offer letter from an employer, the e-receipt from your lunch at a local restaurant, the shipping confirmation email containing your addresses information, are all scanned rather indiscriminately. Where does the data go? How specifically is such data used?

Often, the data is ingested into machine-learning algorithms as well; for example, if you just booked a flight to Jamaica and received a receipt and flight itinerary to your non-privacy friendly email, you may receive a prompt to add the event to your calendar or suggestions for what to do in Jamaica on maps. Likely, it came from scanning the message.

While in 2017, Gmail announced it would stop scanning Gmail messages to sell targeted ads specifically, that did not mean they stopped, well, scanning messages or attachments. Gmail still scans your email for spam and malware, “smart features,” and autocomplete suggestions.

As of November 2023, Outlook and approximately 700+ third parties process Outlook data to complete actions such as storing and accessing information on your device, serve personalized ads and content, and derive analytics/sights.

Additionally, data collected by scans is often stored for undisclosed or varying amounts of time. Even data that is “anonymized” can identify users when enough points are collected over sufficient enough time. Depending on the privacy policy, “anonymized” data may be shared with third parties or used to generate user profiles.

For the majority of users out there, search engines are the gateway to the internet. Search engines often function as the point from which most users browse and visit websites. Queries can range from “best restaurants in my town” to “how to build a gaming pc” and everything in between.

Unfortunately, the most popular search engines out there go great lengths to connect your search queries with your real world identity. Many search engines – especially the dominant search providers – collect personally identifying information (PII) and/or log search queries. In many cases, you can’t opt-out and use the service.

Private search engines respect the privacy of users. Private search engines typically avoid logging queries, associating queries with the user making them, and avoid invasive fingerprinting practices.

Using privates search engines also allows users to escape filter bubbles, or the “algorithm” that suggests content based on search history and past clicks/click-throughs on categorized websites in results. Filter bubbles may also use data aggregated from other services, websites, social media sites to further “personalize” content.

Filter bubbles steadily isolate users, trapping them in an “echo chamber” of what the algorithm believes you want to see based on past data. The more you interact with content, such as clicking or sharing it, the more this content becomes recommended to you – whether you were explicitly searching for it or not.

Ideally, you’d regularly use a search in that maintains its own independent index. However, this is admittedly a rare feat as it takes considerable resources – primarily money – to do so. Unfortunately, such private search engines maintaining a completely independent index are… very hard to come by.

Most private search engines function as metasearch engines; many query Bing (most common) or Google search indexes without collecting/sharing/logging potentially sensitive identifying information or search queries. In most cases, when using private search engines you’ll get similar results to directly searching Bing and Google minus the filter bubble, tracking, keyword logging, location logging, and other privacy-invasive nasties.

It’s great practice to get in the habit of using multiple search engines. Most users will find that some private search engines produce better results depending on keyword or search type – such as image searching – than others.

Of course, this doesn’t mean you can’t have a “go-to” private (meta)search engine, but you could find more sources than you otherwise would using the same search engine that pulls from the same search indices!

On top of logging search queries, the most popular search engines the world uses – such as Google Search and Microsoft Bing – collect more data about users than most would realize. In most cases, to use the service, the option of “opting out” isn’t given to users.

These search engines actively pursue connecting who you are with what you are searching. They may sell or share this information to entities willing to pay – including advertisers, data brokers, and any number of government agencies around the globe.

When using most popular search engines, they collect identifying data or PII. PII collected frequently includes:

- IP address

- Precise geo-location (if GPS is enabled), however can be inferred from connected Wi-Fi networks and cellular towers

- User agent string – usually includes web browser, device, and operating system information

- Unique identifiers, which may (or may not) include identifying cookies

- Demographic information (generally if you are signed into an account)

Even if you use “Incognito Mode” to perform your searches because search history is not saved in the browser, this does not mean the servers carrying out your query do not log queries. Remember, “Incognito Mode” only applies to the browser and its local storage. Often, user search queries are logged on the server side, with little control how they are handled once logged.

Logged queries can be analyzed, shared, sold, and auctioned off. This may seem like no big deal, but logged search queries are often not anonymized by the popular search engines and can be combined with collected identifying information, such as the PII examples above. This information can be data you’ve knowingly provided or data automatically gathered from your browser, operating system, device, or usage habits.

Clearing your Google or Bing search history does not necessarily wipe it or associated data from these search providers’ servers immediately either; for example, Microsoft clearly states in its Privacy Statement (for Bing) that clearing search history does not wipe the data from their logs:

Additionally, in 2020, the United States Department of Justice (DOJ) filed an antitrust suit against Google for monopolizing search and search advertising. During the trial for this antitrust suit beginning in September 2023, it was alleged Google, as part of abusing its dominance as a search provider, used extensive “semantic matching” to serve ecommerce driven results and ads. When these ads were clicked, Google generated revenue from them.

Keyword search warrants also exist. Keyword search warrants pull the information for everyone who searched a term in a defined period of time. They’re served on the service provider – the search engine – not the people performing the searches. Many times, you may not even be aware your PII was handed to authorities in the execution of a keyword search warrant.

Search engine malvertising is a growing threat. Threat actors (hackers and scammers) abuse Google Search and Bing Search ads to peddle phishing pages and malware. These ads can stay up for days, usually appear at the top of the search engine results pages (“Sponsored section”), and can look extremely similar to existing websites and brands. Using a private search engine (usually coupled with adblocking techniques) can alleviate this in some cases.

As mentioned previously, double check you’ve followed the basic cybersecurity guide as well as improving your basic cybersecurity posture also improves your privacy.

Threat modeling is also a viable option – you should consider what you want to accomplish (or mitigate), the resources (often time, money, some sanity) required, and the consequences if you are not successful. Ultimately, threat modeling balances risk. Remember to revisit your threat model periodically.

While or after establishing a super basic threat model, you can also move into other commonly discussed topics in the privacy space:

Use trusted ad/tracker blockers

Blocking programmatic and targeted advertisements is as much a cybersecurity issue as it is a privacy one. Targeted advertisements frequently go lengths to undermine user privacy for marketing, leads, and sale generations.

Targeted and programmatic ads can carry malware or inject unwanted content/code into visited websites. Malvertising subverts user security and privacy. Unwanted code and content injected on websites can introduce security vulnerabilities and enables/facilitates many methods used to track users.

Use secure/private messengers

Using a secure messenger that engages in no/limited (meta)data collection, uses strong encryption protocols, and minimizes unintended data sharing improves your privacy. The key to a “private” messenger is one that relies on no/minimal metadata and uses end-to-end encryption.

Generally, in the privacy community, neither WhatsApp nor Telegram are considered private. WhatsApp’s end-to-end encryption does not apply to message metadata and may be considered flawed, whereas Telegram does not use end-to-end encryption by default. Additionally, Telegram holds the encryption/decryption keys for most data stored on their servers. Both services attach

To get the most out of secure messengers, it helps if contacts in a user’s given social circle also use (or are open to using) a secure messenger. Be brave and be the first!

Use a VPN

A virtual private network (VPN) can be a useful tool in improving privacy (and security), assuming certain criteria are met by both the VPN provider and the user. However, it is not a toggle switch for instant privacy or security – despite what VPN marketing might tell you.

For example, it would make little sense to use a VPN if a user isn’t already forcing HTTPS everywhere or using a privacy-oriented browser. Likewise, it makes little sense to use a VPN provider that logs browsing and connection data or collects PII. Users should employ basic security and privacy practices such as those found in this guide prior to using a VPN.

Users should also evaluate whether a VPN will help in accomplishing their goals derived from their threat models, ideally without being substantially influenced by the superfluous claims of most of the VPN industry by learning the limits of VPNs and understanding how to choose a VPN provider.

Use a privacy-respecting operating system

There are more privacy-friendly operating systems for desktops, serving as viable alternatives to Windows and macOS. Many more private PC operating systems are Linux-based, though not at all are (ex: FreeBSD).

For mobile: On Android devices, users can install mobile privacy-friendly operating systems, assuming their devices are supported.

It’s not possible to install a different operating system on iOS, but users can take steps to improve their privacy on iDevices by using Advanced Data Protection or configuring Safari for privacy. It is not recommended to jailbreak an iOS device.

Use secure/private cloud storage

Many popular cloud storage providers own the encryption/decryption keys for your files – in theory they could access them whenever the “need” arises. On top of this, these cloud providers may use/analyze/share metadata of the files you upload as they see fit – usually according to the super long Acceptable Use and/or Terms and Conditions policies a majority of users do not read.

Encrypted (zero-knowledge) cloud providers encrypt your files in such a way that even their servers are blind to the contents and metadata. This greatly improves user privacy as the contents and metadata of uploaded files, such as photos and important documents containing PII, cannot be seen by the servers.

Alternatively, users can encrypt files prior to upload to any cloud provider for enhanced privacy.

Privacy is a journey. Do not feel as though you must make all changes – even those found in this guide – at once. Small changes are more effective for meaningful, lasting change.

Since most people spend a lot of time in their browsers, whether on a desktop, laptop, tablet, or smartphone, users should ensure their browser both respects their privacy and improves their privacy.

Your email inbox contains so much data on your life, both in the “real-world” and online – using an encrypted email provider erases potentially unwanted data collection and sharing.

Using private search engines helps mitigate tracking, allows users to burst out of filter bubbles, and helps make it harder to connect your searches with your real-world identity.

While privacy is undeniably important, users should also be sure to take basic steps to improving their personal cybersecurity posture. This guide could be combined with Avoid the Hack’s “Personal Cybersecurity for Everyone” guide to yield solid results for both security and privacy improvement without threat modeling.

Remember: #privacymatters

With that said, stay safe out there!

[ad_2]

Source link

avoidthehack.com